By

Byron Edgington

Ever heard this one from another pilot, or possibly even your instructor? Maybe they also told you there's a margin of error built in, or "that's just an engineering number", or perhaps your check's in the mail? It makes me wonder how many pilots are traversing the sky right now feeling, as the industry lingo has it, 'fat, dumb and happy' looking at gauges that are telling them the absolute rock bottom truth, while they're busy ignoring what they're seeing?

Here's my own experience with this conundrum of what I'll refer to as gauge-denial. They say confession is good for the soul. Well, every pilot ought to be forced, on a regular basis, to confess his or her sins, the transgressions they've made in aviation during the past year, and then submit them anonymously for the benefit of all. The following is from my distant past, when I'd been a helicopter pilot for a very short time, but should have known better anyway. It involved a long cross country flight, over a lot of real estate, with no access to a fuel truck, and a fellow pilot who was in deep denial with me.

We'd taken off in our UH-1 Huey from home base around nine a.m. with a couple of brass types aboard, a crewchief, and a full bag of gas. In the UH-1H, a full load of jet fuel will keep the blades turning and Mister Engine happy for about two hours and thirty minutes, give or take. After that time things get very quiet. The 'H' model Huey's fuel tank held 209 gallons. That figure will be important to remember later on.

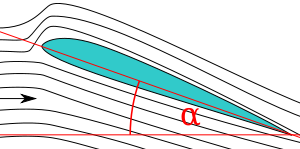

Takeoff and cruise to our destination were uneventful. It was a glorious fall day, and by ten o'clock we were circling our landing spot near the Ohio River. We landed, the generals departed for their appointed rounds, and we shut the Lycoming T53 turbine off to await their return. The flight down had been comfortably quick; a tailwind had assisted our passage, and the Huey--not known for either speed or aerodynamic excellence--had achieved a remarkable 115 knots across the ground. In Vietnam, where I'd flown as recently as one year prior to this incident, that speed was more than sufficient to take me from one end of our area of operations to the other. Indeed, in the war zone, our standard cruise speed in the Huey was 80 knots, or slow enough that the heavily loaded Cobra gunships could keep up with us until they'd unloaded ordnance. This factor may have contributed to my complacency about the fuel situation that day. Another factor, about which the aviation god was notably indifferent, was that I'd survived the war, so I may have been feeling a bit bulletproof. When we landed, the gauge read 740 pounds, or enough for about one hour and fifteen minutes of cruise flight.

The generals returned at eleven o'clock and boarded my Huey. Soon the turbine whined, the blades spun up, and we took off into a moderate headwind, bound for home.

Leveling at 3,000 feet, and getting the cockpit cleaned up, we settled in for what I expected to be a trip north that may be a tad longer than the one south, but not much. At that point in my career I'd not heard the old expression about never making up with tailwind what you lose in headwind, so I had no idea the reverse was equally true. A couple of rough calculations on my trusty whiz wheel, and I began to see the harsh wisdom of that statement. Checking a second, then a third time, I spun the wheel on the E6B device, rechecked the settings, blinked a time or two, and shook my head. According to Mister Flight Computer, our ground speed was a glacial 87 knots. In Vietnam that would have been no cause for concern; over there I'd never flown more than forty miles in any direction or I would have been greeted quite rudely. But this was friendly Ohio, where forty miles was only halfway home. I looked at the fuel gauge: 500 pounds, or enough for about 45 minutes of flight with no reserve. One more look at the map, and my concern mounted a bit more: our course line to home base was exactly 80 nautical miles. Given our ground speed, we had another 50 minutes to fly. This was not rocket surgery; we didn't have enough fuel to get home.

Unless, as a lot of pilots still believe with varying degrees of acceptance, 'those gauges always read a little low', in which case we might squeak by.

As new to the flying game as I was, and as prepared to assume that last adage, as interested in an uneventful flight, and fully vested in getting the generals back to their very important meeting, I opted to press on. The rest is ascribed to experience--how it is gained, and at what expense, if we're lucky.

Eighteen miles from home, the 20 minute fuel low warning light flashed on, its brilliant glow filling up the caution panel like the tilt light on a pinball machine. Great, I thought, reaching for the flight computer. To my consternation, our ground speed had actually decreased a bit, further increasing my store of aviation experience, by teaching me that headwinds always increase as fuel level decreases.

Yet one more spin of the flight computer revealed an ETE of 21 minutes, give or take. By then the warning light had been casting its ardent yellow glow in my cockpit for three minutes. I could have fried an egg in my armpit. Despite the cool fall day, sweat sneaked from under my helmet, and trickled down my back. I hoped the generals and my crewchief didn't notice my discomfort; this was going to be awfully damned close.

Here's the upshot of the tale. We landed on the ramp at home base with the fuel gauge on its absolute zero setting. The 20 minute, low fuel warning light had been alight for 23 minutes. With utter relief, we twisted the throttle off, and the blades wound down. I couldn't state with any degree of precision if the engine had stopped due to my input, or if we'd just flat run out of gas. Watching the fuel truck drive up and stop, I knew the topping off to follow would be very interesting indeed.

The blades stopped, my crewchief tied them down, and the fueler began his ritual. The fuel nozzle slipped into its port, and jet fuel began splashing into the tank, displacing what fumes were left there. I watched the truck's fuel delivery meter race on, clicking along through fifty, one hundred, one-hundred-fifty gallons. As it passed through 190 gallons and never slowed, I knew we'd come damned close to fuel exhaustion. Finally, at 201 gallons the automatic shutoff snapped, and the tank was full. I'd landed the Huey with 8 gallons left in the tank, about enough for two or three minutes of flight. That figure is misleading, however. Could I have hovered along another two or three minutes? No, and here's why: according to the operator's manual, the UH-1 fuel tank has about five gallons of unusable fuel. Thirty seconds or so would have made the difference that day between a landing and an inflight flameout.

I learned a lot on that mission. To plan better; to find fuel somewhere--even a remote spot--to ignore a general's priorities in favor of aviation safety; and to stop listening to those old, tired aviation maxims that give comfort when what we really need is fuel--and a dose of common sense.

Does the gauge 'always read a little low'? It did that day, lucky for me. But the unusable fuel factor could have done me in, regardless. So next time you hear of a margin of error, or a built in engineering factor with the aircraft, take it from me. The best way to stay safe, and to retire, as I did, with little fanfare, and your record intact, is this: build in a little margin of error the other direction. Remember, those fuel gauges always read a little high.

Byron Edgington is a writer, public speaker and retired commercial helicopter pilot. He is also the author of the aviation memoir, The Sky Behind Me to be published soon.

Byron@caffection.com

Article Source: http://EzineArticles.com/?expert=Byron_Edgington

http://EzineArticles.com/?Running-on-Fumes---Those-Fuel-Gauges-Always-Read-a-Little-Low&id=2893301

I have flown many different types of aircraft, and when I was operating both Airline and Air Taxi work single crew it was often slow and ponderous to try and use a check list, especially on simple aircraft like the Islander or Trislander.

I have flown many different types of aircraft, and when I was operating both Airline and Air Taxi work single crew it was often slow and ponderous to try and use a check list, especially on simple aircraft like the Islander or Trislander.